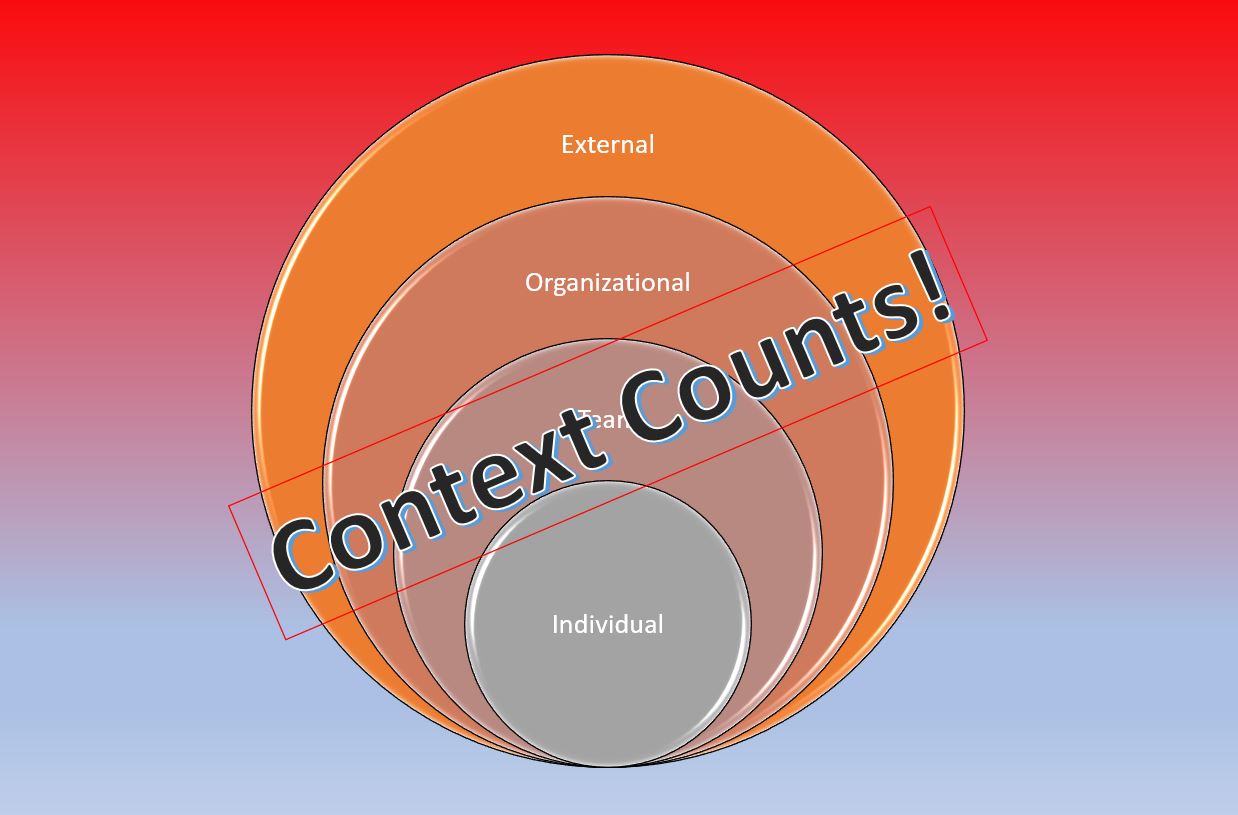

The concept of tailoring has been referenced in all editions of the PMBOK® Guide but the topic starting receiving more coverage in the Sixth Edition and finally was given a full section in the most recent edition. But before we can start tailoring we need to answer the question of what context needs to be addressed.

The concept of tailoring has been referenced in all editions of the PMBOK® Guide but the topic starting receiving more coverage in the Sixth Edition and finally was given a full section in the most recent edition. But before we can start tailoring we need to answer the question of what context needs to be addressed.

External

Outside the performing and receiving organizations, the environment within which the project is being executed needs to be considered. These form the external portion of the Enterprise Environmental Factors (EEFs) which are frequently referenced in the PMBOK Guide.

The industry we are in will influence and constrain our approach. In the pharmaceutical industry, validation documentation for projects which are involved in the testing or production of products is required whereas in other industries, less formality might be needed.

What’s going on in the world also needs to be considered. The COVID-19 pandemic imposed requirements on teams to work in a dispersed manner even if they could have previously been co-located.

Organizational

The context of both the performing and receiving organizations will influence project approaches. Organizational Process Assets (OPAs) such as standards and policies apply, but also factors such as where stakeholders are located, funding availability, and what else is going on in the organizations needs to be considered. For example, running a project in a long-standing, large organization usually involves heavier governance and oversight than that for a startup.

The terms and conditions from contracts established between the performing and receiving organizations will also affect how the work is done. For example, while team members from the performing organization might have preferred to use one set of tools for managing their work flow, their contract with the receiving organization might specify the requirement to use an alternate tool set.

Team

Characteristics such as a team’s longevity, its culture, factors such as the level of psychological safety and trust within it, and its makeup will affect our tailoring approach.

We might want to encourage team members to become generalizing specialists but if some of the team members fall under a union contract which rigidly defines the type of work they can do, this might not be possible.

If the team is new and the team members have not had a chance to work together in the past, working agreements and handoff criteria might need to be more explicitly documented than for a long standing team.

Individual

We need to consider the context of each team member as well as that of our stakeholders.

One of the principles from the Manifesto for Agile Software Development is “The most efficient and effective method of conveying information to and within a development team is face-to-face conversation.”. But what happens if one or more of our team members are extremely introverted and are uncomfortable with prolonged face-to-face work? Similarly, we might want to do an experiment in pairing or mobbing, but if the individual personalities and preferences of team members don’t support this, the experiment might fail.

Information radiators such as a product canvas or a work board might be sufficient for most stakeholders to understand what’s going on but if one of our key stakeholders insists on getting more context about project status we might need to produce a status report or hold a regular meeting to meet their needs.

Context (at all levels) counts.

(If you liked this article, why not read my book Easy in Theory, Difficult in Practice which contains 100 other lessons on project leadership? It’s available on Amazon.com and on Amazon.ca as well as a number of other online book stores)

After daily coordination events (a.k.a. Scrums, standups or huddles), velocity might be the most misused tool by teams new to agile and the stakeholders supporting them. Used appropriately, it can help a team to understand how much work they can complete in a fixed amount of time and thus could be used to forecast when they might be done with a release. However, being able to do so requires that three critical prerequisites are met. If any of these are not,

After daily coordination events (a.k.a. Scrums, standups or huddles), velocity might be the most misused tool by teams new to agile and the stakeholders supporting them. Used appropriately, it can help a team to understand how much work they can complete in a fixed amount of time and thus could be used to forecast when they might be done with a release. However, being able to do so requires that three critical prerequisites are met. If any of these are not,  An

An